Feeding Low-Energy Diet Improves Broiler Productivity Index of Chickens Reared under Semi-Arid Environment

byAbstract

This objective of the study was to investigate the effects of season and energy levels on the broiler productivity index (BPI) in the semi-arid environment. The study was conducted in three different seasons (hot, rainy and cold seasons). A total of 2,025 boiler chickens comprising three strains (Arbor Acre, Marshall and Hubbard) were used. Of this, 675 were used per season, with 225 birds from each strain. The birds were fed diets containing three energy levels: low (LE), medium (ME), and high (HE). Temperature-humidity index (THI) of the seasons was computed to characterize the thermal comfort of the chickens across the seasons. Results indicated that the chickens were reared under severe heat stress (THI > 30), moderate heat stress (THI 27.8–28.8), and thermo-neutral conditions (THI < 27.8) during the hot, rainy, and cold seasons, respectively. Additionally, energy level and season significantly affected the BPI of the chickens (p < 0.05). Birds fed the LE diet had a higher BPI than those fed the other energy levels. Furthermore, birds reared during the cold season exhibited a higher BPI than those reared in the other seasons. Therefore, feeding the LE diet improved the BPI of birds across all seasons.

Keywords: energy level; heat stress; season; broiler productivity index

1. Introduction

Poultry production in tropical environments suffers substantial losses due to environmental stressors such as high ambient temperature and relative humidity, which make production highly challenging [1,2]. The semi-arid environment, in particular, hinders broilers from achieving their expected body weight at specific ages, thereby reducing overall productivity and making the broiler industry less profitable in the region [3,4]. This peculiar situation necessitates the evaluation of different broiler strains fed varying energy levels across the distinct seasons of the semi-arid environment [5]. The climate in such regions is characterized by three distinct seasons—hot, rainy, and cold—each presenting unique challenges to broiler production. This underscores the importance of studying seasonal variations and their implications for broiler performance [6–8].

Several broiler strains have been developed to enhance growth rate, feed conversion efficiency, and survivability [9–11]. However, most of these strains were developed under temperate climates or environmentally controlled conditions [8] and may therefore not perform optimally when exposed to the natural semi-arid production environment [12–14]. Common broiler strains raised by farmers in the region include Arbor Acre, Marshall, Hubbard, Ross, and Anak [15].

In addition to strain differences, dietary energy content plays a pivotal role in achieving the desired production performance for which broilers are genetically developed [12,16–18]. Energy requirements of broiler chickens are largely influenced by environmental conditions, stage of growth, and production objectives [17,19,20]. Several studies have indicated that broilers reared under hot and humid conditions experience thermal stress, which compromises their performance due to increased metabolic effort in thermoregulation [8]. Under such environmental conditions, energy requirements for broilers have been reported to range from 2800 to 3200 ME kcal/kg [21,22]. This variation is primarily attributed to seasonal fluctuations in temperature and relative humidity.

Therefore, the present study investigated the performance variability among commonly reared broiler strains under different dietary energy levels across the distinct seasons of the semi-arid environment, with the aim of identifying the most suitable strain and dietary energy level for each season.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

The study was conducted at the Poultry Production Unit of the Livestock Teaching and Research Farm, Department of Animal Science, Usmanu Danfodiyo University, Sokoto. Sokoto State lies in the north-western region of Nigeria (12°00′00″ N to 13°05′00″ N, 4°08′00″ E to 6°04′00″ E). The area falls within the Sudan savannah ecological zone, characterized by distinct wet and dry seasons. The hot season extends from March to May, followed by the rainy season from June to September. The cold season (harmattan) occurs between November and February, during which temperatures are considerably lower compared to the other seasons.

Ambient temperatures during the hot period can rise to 43.6°C, while minimum temperatures may drop to about 12.8°C during harmattan [23]. Relative humidity averages approximately 20% in April and may fluctuate diurnally from 30% to as low as 10% in the afternoon during the dry, dusty harmattan winds. In contrast, humidity levels during the rainy season can reach up to 82% in August [24,25].

2.2. Experimental Design

The trial was conducted across three seasons—hot, rainy, and cold—using three broiler strains (Hubbard, Arbor Acres, and Marshall), with 225 birds per strain in each season, making a total of 2,025 broiler chickens. The birds were arranged in a factorial layout under a completely randomized design. Three dietary treatments were offered to each strain in each season. Each dietary treatment had five replicates with 15 birds per replicate.

For the starter phase, the three dietary energy levels were formulated as 2,900 kcal/kg ME (LE: low energy), 3100 kcal/kg ME (ME: medium energy), and 3300 kcal/kg ME (HE: high energy). Similarly, during the finisher phase, the energy levels were 2800 kcal/kg ME (low energy), 3000 kcal/kg ME (medium energy), and 3200 kcal/kg ME (high energy). The diet formulation used in this study was identical across all seasons and has been described in detail previously [26].

2.3. Experimental Birds and Their Management

The birds used for this experiment consisted of three strains, namely Hubbard, Marshall, and Arbor Acres broiler strains. The day-old chicks were of the same age. The experimental birds were fed a commercial diet during an adjustment period of three days after purchase to reduce stress due to transportation. During this period, they were administered vitamins as anti-stress agents. The birds were later weighed and allotted to their replicate groups. Vaccinations, antibiotics and coccidiostats were used as per the farm protocols. The birds were housed in deep litter pens with open-sided walls. The pens were washed, cleaned, fumigated, and disinfected prior to the arrival of the birds. Wood shavings were used as litter material. This procedure was repeated in each season.

2.4. Experimental Period and Duration

The hot season trial was conducted between March and April, which was characterized by high ambient temperature and low humidity, while the rainy season trial was conducted between July and August and was characterized by high rainfall, temperature fluctuations, and high humidity. Similarly, the cold season trial was carried out from November through January and was characterized by low ambient temperature and relative humidity. In all seasons, the trial lasted for 56 days (8 weeks).

2.5. Data Collection

Feed intake was recorded daily by subtracting the leftover feed from the feed offered the previous day. The birds were weighed weekly, and weight gain was determined. Feed conversion ratio was calculated using feed intake and weight gain for each replicate. Similarly, the data obtained on final weight, mortality (livability), and feed conversion ratio were used to compute the broiler productivity index (BPI) for each replicate using the formula:

BPI = [(Live weight × Survivability)/ (FCR × Rearing period(days))] × 100

Where FCR represents feed conversion ratio.

A Metro-clock weather station was used to monitor weather variables, including temperature and relative humidity of the immediate environment, hourly, from which daily means were computed. These variables were used to calculate the Temperature-Humidity Index (THI) following Lallo et al. [27] using the formula below:

THI= 0.85T + 0.15RH

Where T is ambient temperature in °C and RH is relative humidity in %.

2.6. Data Analysis

Data for BPI were subjected to analysis of variance (ANOVA) using StatView software (SAS Institute Inc., 1998), and the least significant difference (LSD) test was used for mean separation. Daily THI data for all days during the study were plotted to characterize the thermo-comfort conditions of the rearing seasons according to Tirawattanawanich et al. [28].

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Temperature-Humidity Index during the Hot, Rainy, and Cold Seasons of Broiler Rearing

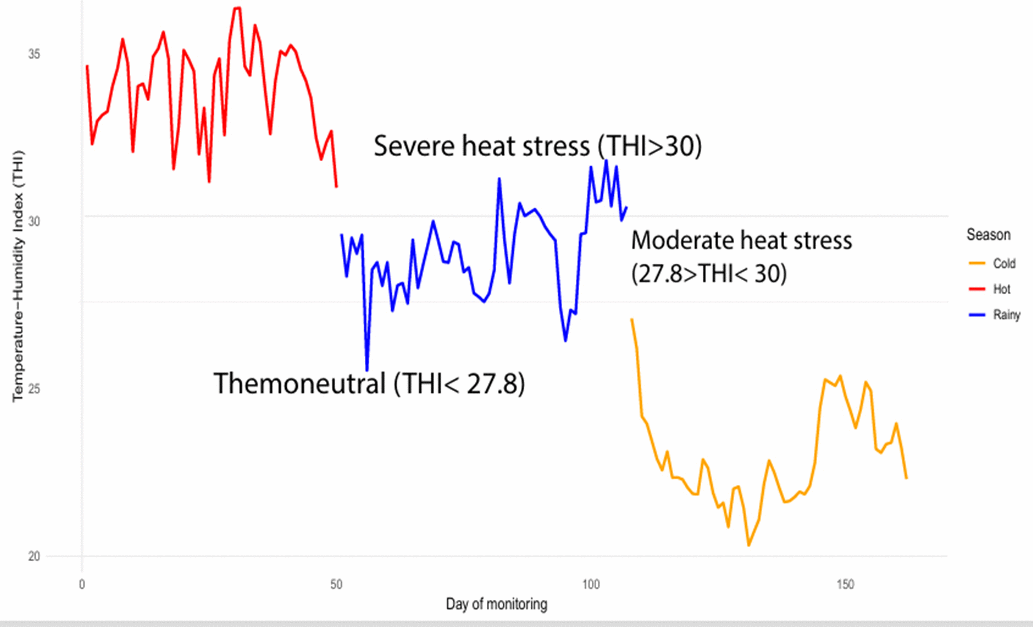

The analysis of temperature-humidity index (THI) data highlights significant seasonal variations that impact poultry health and performance (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Temperature-humidity index (THI) of chicken rearing pens during the hot, rainy, and cold seasons.

During the hot season, THI levels frequently exceed 30, resulting in severe heat stress, which adversely affects growth and metabolic functions in broilers[29,30]. Severe heat stress also impairs immune function [31]. In contrast, the rainy season shows fluctuating THI levels ranging from comfort (THI ≤ 27.8) to moderate heat stress (THI 27.9–28.8), which continues to challenge nutrient digestibility, absorption, and overall performance [30,32]. The cold season, characterized by THI below 27.8, supports optimal growth and health, minimizing stress-related issues [29,33].

3.2. Broiler Productivity Index

The results on the effect of energy level, season, and strain on BPI are presented in Table 1. The low-energy diet was observed to have a significantly higher (p < 0.05) BPI value than both the medium- and high-energy diets. However, BPI did not differ significantly (p > 0.05) between the medium- and high-energy diets. Similarly, the cold season recorded a significantly higher (p < 0.05) BPI value than either the hot or rainy season, but there was no significant difference (p > 0.05) between the hot and rainy seasons with respect to BPI.

| Factor | BPI (Mean) | SEM | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Energy level | 0.042 | ||

|

High |

332.949 b | ||

|

Medium |

333.847 b | ||

|

Low |

405.386 a | 28.430 | |

| Season | < 0.001 | ||

|

Hot |

324.137 b | ||

|

Rainy |

298.580 b | ||

|

Cold |

449.459 a | 21.193 | |

| Strain | 0.091 | ||

|

Arbor Acre |

355.513 | ||

|

Hubbard |

357.417 | ||

|

Marshall |

359.252 | 25.789 |

Means with different superscripts (a, b) differ significantly (p < 0.05).

Low-energy diets resulted in significantly higher BPI values (p < 0.05) compared to medium- and high-energy diets, suggesting that lower energy content promotes greater feed intake. The inverse relationship between energy content and feed intake is particularly important in hot environments, where birds may struggle with thermal stress [34]. Eldelita and Naas [35] reported a significant difference (p < 0.05) in BPI between broilers reared in regulated housing and those kept under the naturally hot and humid environment of Brazil, which is in line with the findings of this study. In another study [36], they reported a significant (p < 0.05) effect of strain, environmental temperature, and ventilation on broiler productivity, which partly agrees with the findings of the current study.

In alignment with this observation, the cold season recorded a markedly higher BPI value of 449.459 (p < 0.05), which was considered exceptional when compared with the BPI values obtained during the hot (341.137) and rainy (298.580) seasons. This pattern underscores the environmental challenges associated with both the hot and rainy seasons in semi-arid ecosystems, which may negatively affect broiler productivity. These adverse effects are likely attributable to elevated temperatures during the hot season and pronounced temperature fluctuations combined with high humidity levels during the rainy season.

Such environmental stressors can influence feed consumption and survivability, thereby affecting performance indicators such as live weight and feed conversion ratio, ultimately resulting in reduced BPI values in both the hot and rainy seasons. Notably, Hayati and Atilgan [37] reported that broiler production is more viable during the summer months than in winter, which contrasts with the findings of the present study. However, this discrepancy may be attributed to differences in production scale, the specific variables considered in calculating production efficiency, and variations in environmental conditions encountered across studies.

4. Conclusions

In conclusion, the study revealed that under semi-arid conditions, low-energy diets resulted in a higher productivity index in broilers. Additionally, the hot and rainy seasons markedly reduced the productivity index. Considering the importance of dietary energy level and seasonal effects, targeted feeding strategies should be implemented, and appropriate measures should be adopted to mitigate the impact of heat stress during hot and humid seasons in semi-arid regions. Since low-energy diets were found to improve productivity under hot semi-arid conditions, future research should focus on optimizing season-specific feeding regimes.

Data Availability Disclosure:

Funding and Support Disclosure

References

- Netshipale, A. J.; Benyi, K.; Baloyi, J. J.; Mahlako, K. T.; Mutavhatsindi, T. F. Responses of two broiler chicken strains to early-age skip-a-day feed restriction in a semi-arid subtropical environment. Afr. J. Agric. Res. 2012, 7, 6523–6529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oluyemi, J. A.; Roberts, F. A. Poultry production in warm wet climates, 2nd ed.; Spectrum Books Ltd.: Ibadan, Nigeria, 2000; ISBN 978-0-333-25312-0. [Google Scholar]

- Abioja, M. O.; Abiona, J. A. Impacts of climate change to poultry production in Africa: Adaptation options for broiler chickens. In African handbook of climate change adaptation; Leal Filho, W., et al., Eds.; Springer: Cham, 2021; pp 275–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kpomasse, C. C.; Oke, O. E.; Houndonougbo, F. M.; Tona, K. Broiler production challenges in the tropics: A review. Vet. Med. Sci. 2021, 7, 831–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarma, M.; Borah, M. K.; Kalita, K. P.; Mahanta, J. D.; Kalita, N.; Talukdar, J. K.; Deka, P.; Amonge, T. K.; Islam, R. Effect of season on performance of broiler chicken under deep litter system of management in Assam. Int. J. Livest. Res. 2019, 9, 246–253. [Google Scholar]

- Gholami, M.; Chamani, M.; Seidavi, A.; Sadeghi, A. A.; Aminafschar, M. Effects of stocking density and climate region on performance, immunity, carcass characteristics, blood constitutes, and economical parameters of broiler chickens. Rev. Bras. Zootec. 2020, 49, e20190049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soleimani, A. F.; Zulkifli, I.; Omar, A. R.; Raha, A. R. Physiological responses of 3 chicken breeds to acute heat stress. J. Poult. Sci. 2011, 90, 1435–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Dunshea, F. R.; Warner, R. D.; DiGiacomo, K.; Osei-Amponsah, R.; Chauhan, S. S. Impacts of heat stress on meat quality and strategies for amelioration: a review. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2020, 64, 1613–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzala, M.; Janicki, B.; Czarnecki, R. Consequences of different growth rates in broiler breeder and layer hens on embryogenesis, metabolism and metabolic rate: a review. Poult. Sci. 2015, 94, 728–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghayas, A.; Hussain, J.; Mahmud, A.; Jaspal, M. H. Evaluation of three fast- and slow-growing chicken strains reared in two production environments. S. Afr. J. Anim. Sci. 2020, 50, 378–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawab, A.; Ibtisham, F.; Li, G.; Kieser, B.; Wu, J.; Liu, W.; Zhao, Y.; Nawab, Y.; Li, K.; Xiao, M.; An, L. Heat stress in poultry production: mitigation strategies to overcome the future challenges facing the global poultry industry. J. Therm. Biol. 2018, 78, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attia, Y. A.; Saber, S. H. Broiler tolerance to heat stress at various dietary protein/energy levels. Eur. Poult. Sci. 2017, 81, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyoni, N. M. B.; Garba, S.; Archer, E. R. M. Heat stress and chickens: climate risk effects on rural poultry farming in low-income countries. Clim. Dev. 2019, 1, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soren, N. M. Nutritional manipulations to optimize productivity during environmental stresses in livestock. In Environmental Stress and Amelioration in Livestock Production; Sejian, V., Naqvi, S., Ezeji, T., Lakritz, J., Lal, R., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, B. L. Effects of ambient temperatures and early open-field response on the behavior, feed intake and growth of fast and slow growing broiler strains. Animal 2012, 6, 1460–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Classen, H. L. Diet energy and feed intake in chickens. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2017, 233, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakomura, N. K.; Longo, F. A.; Oviedo-Rondón, E. O.; Boa-Viagem, C.; Ferraudo, A. Modeling energy utilization and growth parameter description for broiler chickens. Poult. Sci. 2005, 84, 1363–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, X.; Xin, H. Acute synergistic effects of air temperature, humidity, and velocity on homeostasis of market size broilers. Trans. ASAE 2003, 46, 491–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Moneim, E. M.; Shehata, A. M.; Khidr, R. E.; Paswan, V. K.; Ibrahim, N. S.; El-Ghoul, A. A.; Aldhumri, S. A.; Gabr, S. A.; Mesalam, N. M.; Elbaz, A. M.; Elsayed, M. A.; Wakwak, M. M.; Ebeid, T. A. Nutritional manipulation to combat heat stress in poultry – a comprehensive review. J. Therm. Biol. 2021, 98, 102915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murtala, M.; Iguisi, E. O.; Ibrahim, A. A.; Yusuf, Y. O.; Inobeme, J. Spatio-temporal analysis of drought occurrence and intensity in Northwest zone of Nigeria. Dutse J. Pure Appl. Sci. 2018, 4, 111–129. [Google Scholar]

- Borges, S. A.; Fischer, A. V.; Ariki, J.; Hooge, D. M.; Cummings, K. R. Dietary electrolyte balance for broiler chickens under moderately high ambient temperatures and relative humidity. Poult. Sci. 2003, 82, 301–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazalah, A. A.; Abd-Elsamee, M. O.; Ali, A. M. Influence of dietary energy and poultry fat on the response of broiler chicks to heat therm. Int. J. Poult. Sci. 2008, 7, 355–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.; Murtala, M. Climate change in extreme northern Nigeria: evidence from rainfall trend in Sokoto State. Dutse J. Pure Appl. Sci. 2019, 5, 187–194. [Google Scholar]

- Gwani, M.; Abubakar, G. A.; Fatigue, A. T.; Adebiyi, S. J.; Joshua, B. Analysis of monthly variation of relative humidity and temperature of Sokoto, Nigeria. World J. Eng. Pure Appl. Sci. 2013, 3, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Nambapana, M.; Jayasena, D. Heat stress management via nutritional strategies for broilers. In Modern Technology and Traditional Husbandry of Broiler Farming; Al-Marzooqi, W., Ed.; Agricultural Sciences; IntechOpen: 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliyu, S.; Bashar, Y. A.; Abubakar, A.; Abdullahi, A. U.; Ribah, M. I.; Garba, S.; Mani, A. Performance of some broiler strains fed varying energy levels in wet season of semi-arid Sokoto, Nigeria. Res. Agric. Livest. Fish. 2018, 5, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lallo, C.; Cohen, J.; Rankine, D.; Taylor, M.; Campbell, J.; Stephenson, T. Characterizing heat stress on livestock using the temperature humidity index (THI)- prospects for a warmer Caribbean. Reg. Environ. Change 2018, 18, 2329–2340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirawattanawanich, C.; Chantakru, S.; Nimitsantiwong, W.; Tongyai, S. The effects of tropical environmental conditions on the stress and immune responses of commercial broilers, Thai indigenous chickens, and crossbred chickens. J. Appl. Poult. Res. 2011, 20, 409–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apalowo, O. O.; Ekunseitan, D. A.; Fasina, Y. O. Impact of heat stress on broiler chicken production. Poultry 2024, 3, 107–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemanth, M.; Venugopal, S.; Devaraj, C.; Shashank, C. G.; Ponnuvel, P.; Mandal, P. K.; Sejian, V. Comparative assessment of growth performance, heat resistance and carcass traits in four poultry genotypes reared in hot-humid tropical environment. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 2024, 108(5), 1510–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nangsuay, A.; Molenaar, R.; Meijerhof, R.; van den Anker, I.; Heetkamp, M. J. W.; Kemp, B.; van den Brand, H. Differences in egg nutrient availability, development, and nutrient metabolism of broiler and layer embryos. Poult. Sci. 2015, 94, 415–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H. R.; Ryu, C.; Lee, S. D.; Cho, J. H.; Kang, H. Effects of heat stress on the laying performance, egg quality, and physiological response of laying hens. Animals 2024, 14, 1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perween, S.; Kumar, K.; Chandramoni, K. S.; Kumar, S.; Singh, P. K.; Kumar, M. D. Effect of feeding different dietary levels of energy and protein on growth performance and immune status of Vanaraja chicken in the tropic. Vet. World 2016, 9, 893–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Abdullatif, A.; Hussein, E.; Maleldin, G. A.; Akasha, M.; Al-Badwi, M.; Ali, H.; Azzam, M. Evaluating rice bran oil as a dietary energy source on production performance, nutritional properties and fatty acid deposition of breast meat in broiler chickens. Foods 2023, 12, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldelita, A. P. F.; Naas, I. A. Broiler production efficiency: an analysis using thermal infrared images. Rev. Bras. Eng. Biossist. 2022, 16, e1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mir, N. A.; Rafiq, A.; Kumar, F. Determinants of broiler chicken meat quality and factors affecting them: a review. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 54, 2997–3009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koknaroglu, H.; Atilgan, A. Effect of season on broiler performance and sustainability of broiler production. J. Sustain. Agric. 2007, 31, 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Copyright: © 2025 by the authors.

License: This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International.CC BY 4.0

Publisher: Insights Academic Publishing (IAP), Lahore, Pakistan.